艾米丽卡尔(Emily Carr)

艺术家: 艾米丽卡尔

生于: 1871年12月13日;加拿大不列颠哥伦比亚Victoria

卒于: 1945年3月02日;加拿大不列颠哥伦比亚Victoria

国籍: 加拿大

流派: 后印象派,现代主义

领域: 绘画

受影响: Lawren Harris,安德烈·德朗,保罗·高更,Post-Impressionism

影响: Jessica Stockholder

老师: Lawren Harris,Harry Phelan Gibb,Algernon Talmage

朋友: Albert Julius Olsson

机构: 学院的托盘,法国巴黎,colarossi学院,法国巴黎,旧金山艺术学院(SFAI),旧金山,加州,美国西敏艺术学院,伦敦,英国

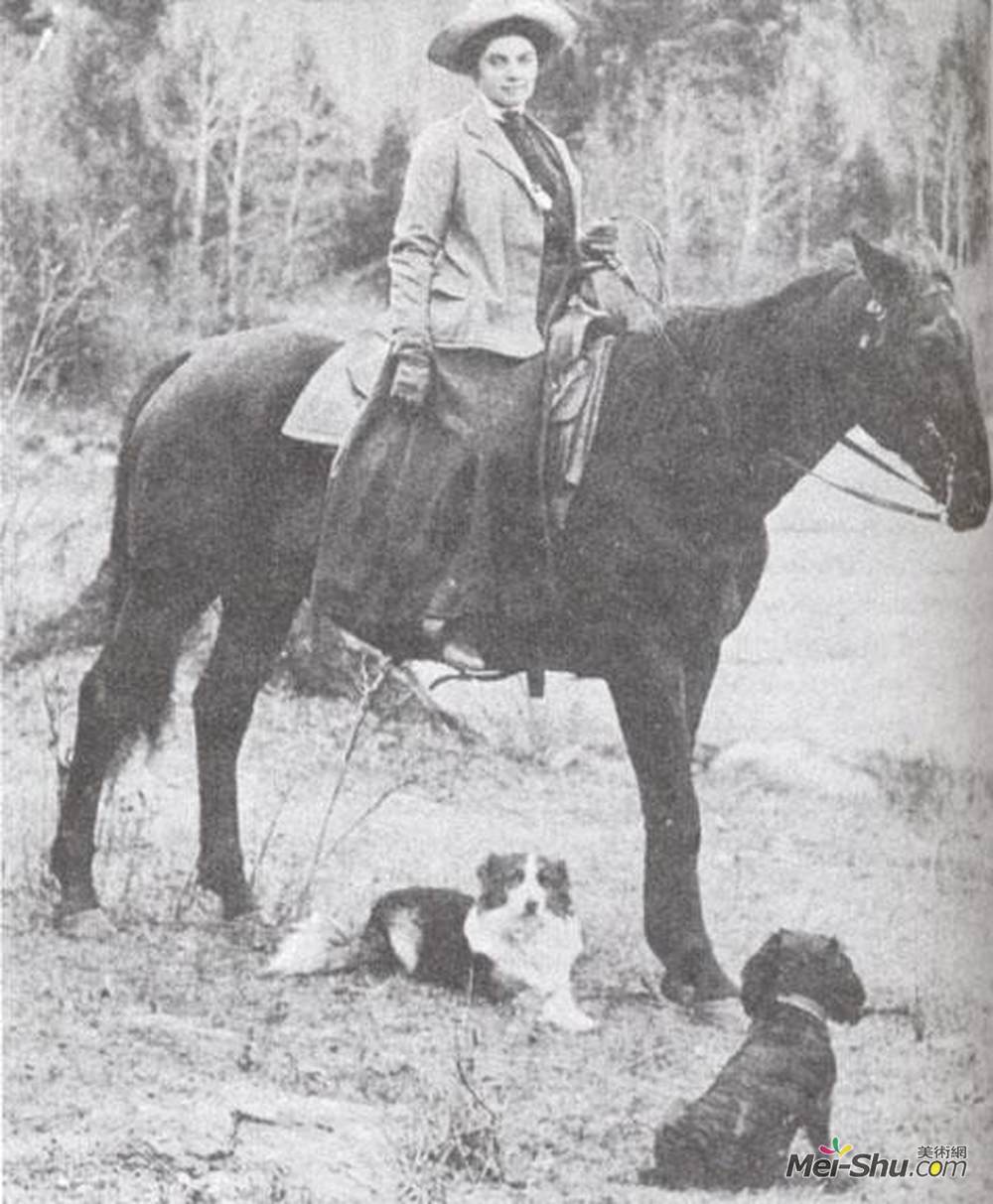

埃米莉·卡尔被认为是加拿大的一位主要艺术家,她描绘了太平洋西北部及其土著文化。作为加拿大现代主义和后印象主义绘画风格的先驱之一,她直到晚年才为人们所认识。

Carr于1871年出生于不列颠哥伦比亚省的维多利亚。她对艺术的爱好得到了她的父亲Richard Carr的大力鼓励,她是一个批发商人。1890年父母双亡后,她开始认真地追求艺术,并在旧金山艺术学院学习了两年。在26岁的时候,Carr参观了位于温哥华岛西海岸的尤克卢利特附近的一个小村庄。在那里,她勾画了土著人的生活。她到阿拉斯加去画村民的日常活动,促进了她对印度人生活方式的兴趣。

1899年,卡尔去英国在伦敦的威斯敏斯特艺术学院学习。在英国,她与圣艾夫斯学校的艺术家Julius Olsson和Algernon Talmage结交并工作。当她回到加拿大时,卡尔建立了自己的职业艺术家。她在温哥华女子艺术俱乐部当老师,在那里,由于吸烟习惯和诅咒,她在学生中极不受欢迎,这最终导致她辞职。在和夏洛特女王群岛和上斯基纳河的许多印度村庄幽会之后,卡尔于1910年再次去了欧洲,在巴黎的Acad&mie Colarossi学习。她还从Harry Phelan Gibb的私人课,影响她的调色板,添加了更鲜艳的颜色。她还受到法国后印象派和野兽派的影响,1912年返回加拿大后,她展出了70幅“法国时期”的油画和水彩画,显示了这些影响。然而,她大胆的新风格并未受到加拿大人的赞赏。在接下来的15年里,Carr画得不多。她经营着一个寄宿舍,参加了一个短篇小说写作课程,在旧金山做了一些不同的工作,比如为圣弗朗西斯酒店做装饰画,为西方妇女周刊画卡通画。1927,卡尔出席了加拿大国家美术博物馆西海岸土著艺术展。在那里,她会见了Lawren Harris和其他七人的成员,在加拿大最著名的现代画家在那个时候。他们独特的加拿大艺术给她留下了深刻的印象,并引发了她创作生涯中最丰富的时期。在过去的十年里,她掌握了土著居民日常生活、传统和文化的场景。以劳伦·哈里斯为导师,卡尔开始绘画大胆的、几乎是幻觉的画布,许多人用它来辨认她——设置在森林深处或被遗弃的土著村庄遗址上的土著图腾柱的画。

一年或两年后,留下的土著人致力于自然主题。从1928年开始,像加拿大国家美术馆和华盛顿的美国艺术家联合会等具有区域意义的展览开始受到批判性的认可和曝光。甚至有偶尔的销售,虽然从来都不足以改善她的财务状况。在充分掌握她的才华和深化的视野中,她继续创作大量绘画作品,自由地表现西方森林、漂浮的木质海滩和广阔的天空的巨大节奏,如

Artist :Emily Carr

Additional Name :Emily Carr

Born : Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

Died : Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

Nationality :Canadian

Art Movement :Post-Impressionism,Modernism

Influenced by :lawren-harris,andre-derain,paul-gauguin,artists-by-art-movement/post-impressionism

Influenced on :jessica-stockholder

Teachers :lawren-harris,harry-phelan-gibb,algernon-talmage

Friends and Co-workers :albert-julius-olsson

Art institution :Académie de La Palette, Paris, France,Académie Colarossi, Paris, France,San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), San Francisco, CA, US,Westminster School of Art, London, UK

Emily Carr is considered to be a major Canadian artist for her depiction of the landscapes of Pacific Northwest and its aboriginal culture. Being one of the pioneers of Modernist and Post-Impressionist styles of painting in Canada, she was not recognized until late in her life.

Carr was born in Victoria, British Columbia in 1871. Her inclination to art was duly encouraged by her father, Richard Carr, a wholesale merchant. After the death of both her parents in 1890, she started to pursue art seriously, and studied at the San Francisco Art Institute for two years. At the age of 26, Carr visited a small village near Ucluelet located on the western coast of the Vancouver Island. There she sketched the lives of the Nootka people, indigenous to the land. Her interest in the lifestyle of Indian people was promoted by her trip to Alaska, where she spent days sketching the daily activities of the villagers.

In 1899, Carr went to the UK to study at the Westminster School of Art in London. In England she befriended and worked with Julius Olsson and Algernon Talmage, artists of the St. Ives School. By the time she returned to Canada, Carr established herself as a professional artist. She worked as a teacher at the Ladies Art Club in Vancouver, where she was highly unpopular among the students due to her smoking habits and cursing, that eventually led her to resign from her job.

After her tryst with many Indian villages in the Queen Charlotte Islands and the Upper Skeena River, Carr once again went to Europe in 1910, to study at the Académie Colarossi in Paris. She also took private lessons from Harry Phelan Gibb who influenced her palette adding there more vibrant colors. She was also influenced by French Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, and, after returning back to Canada in 1912, she exhibited 70 oils and watercolors of her “french period”, showing those influences. However, her bold new style was not appreciated by Canadians.

During the next 15 years, Carr did not paint much. She run a boarding house, took a short-story writing course, and spent some time in San Francisco doing different jobs, like painting decorations for the St. Francis Hotel and drawing cartoons for Western Woman’s Weekly. In 1927 Carr attended an exhibition of West Coast Aboriginal art in National Gallery of Canada. There she met Lawren Harris and other members of the Group of Seven, the most recognized modern painters in Canada at that time. Their distinctively Canadian art impressed her greatly, and triggered the most prolific period of her creative career. Throughout the decade, she mastered the scenes from the daily lives, traditions and culture of the indigenous Americans. With Lawren Harris as her mentor, Carr began to paint bold, almost hallucinatory canvases with which many people identify her - paintings of Aboriginal totem poles set in deep forest locations or the sites of abandoned Indigenous villages.

After a year or two Carr left Aboriginal subjects to devote herself to nature themes. From 1928 on, critical recognition and exposure in exhibitions of more than regional significance, like the National Gallery of Canada and the American Federation of Artists in Washington, D.C., began to come her way. There was even the occasional sale, though never enough to improve her financial situation. In full mastery of her talents and with deepening vision, she continued to produce a great body of paintings freely expressive of the large rhythms of Western forests, driftwood-tossed beaches and expansive skies, like

In 1937, Carr suffered her first heart attack, which marked the beginning of a decline in her health and a lessening of the energy required for painting. Artworks from her last decade, like